The need for a learning module on evaluation has been identified as a priority for both researchers and peer reviewers. In response to the myriad of challenges facing the health system, both researchers and health system managers are proposing significant changes to current clinical, management and public health practice. This requires timely and rigorous assessment of current programs and innovations. Evaluation is a useful strategy for generating knowledge that can be immediately applied in a specific context, and, if certain evaluation approaches are used, can also generate transferable knowledge useful to the broader health system.

In addition to the common need for some research proposals to include an evaluation component, funders are also initiating funding opportunities that focus on trialing innovations and moving knowledge into action. These proposals, by their nature, require well-designed robust evaluation plans if useful knowledge is to be gained. However, many researchers (like health system managers) have limited evaluation knowledge and skills.

The purpose of this learning module, therefore, is to build knowledge and skill in the area of evaluation of health and health research initiatives (including knowledge translation initiatives).

Objectives of the module are to:

This learning module will:

While it will provide a brief overview of key concepts in evaluation, and is informed by various evaluation approaches (theories), the primary purpose of this module is to serve as a practical guide for those with research skill but limited experience conducting evaluations. While this module focuses on evaluation in the context of health research and knowledge translation, it is important to keep in mind that there are multiple evaluation approaches, theories and methods appropriate for different contexts.

Because of increasing awareness of the benefits of including knowledge users 1 as partners in many evaluation activities, the module also includes additional guidance for those conducting evaluation in collaboration with health system or other partners.

The module does not attempt to address all the important topics in evaluation design (e.g. how to minimize and control bias, develop a budget, or implement the evaluation plan). This is because the resource is designed for researchers – and it is assumed that the readers will be equipped to address these issues. In addition, while the steps in designing an evaluation plan are outlined and elaborated, the module does not provide a 'template' that can be applied uniformly to any evaluation. Rather, it provides guidance on the process of developing an evaluation plan, as evaluation design requires the creative application of evaluation principles to address specific evaluation questions in a particular context.

This module is divided into five sections. Section 1: Evaluation: A Brief Overview provides a short overview of evaluation, addresses common misconceptions, and defines key terminology that will be used in the module. This is followed by Section 2, Getting started, whichprovides guidance for the preliminary work that is required in planning an evaluation, and Section 3, Designing an Evaluation, which will lead you through the steps of developing an evaluation plan.

Section 4, Special Issues in Evaluation discusses some of the ethical, conceptual and logistical issues specific to evaluation. This is followed by Section 5: Resources, which includes a glossary, a checklist for evaluation planning and sample evaluation templates.

Throughout the module, concepts will be illustrated with concrete examples – drawn from case studies of actual evaluations. While based on real-life evaluations, they have been adapted for this module in order to maintain confidentiality. A summary of these cases is found on the following page.

A provincial health department contracts for an evaluation of three different models of care provided to hospitalized patients who were without a family physician to follow their care in hospital (unassigned patients). In addition to wanting to know which models 'work best' for patients, the province is also interested in an economic evaluation, as each of the models has a different payment structure and overall costs are not clear.

There is a decision to pilot a commercially developed software program that will combine computerized order entry and physician decision support for test ordering. The decision-support module is based on evidence-based guidelines adopted by a national medical association. Funders require an evaluation of the pilot, as there is an intention to extend use across the region and into other jurisdictions if the results of the evaluation demonstrate that this is warranted.

The current field of evaluation has emerged from different roots, overall purposes and disciplines, and includes many different "approaches" (theories and models). Various authors define evaluation differently, categorize types of evaluation differently, emphasize diverse aspects of evaluation theory and practice, and (because of different conceptual frameworks) use terms in very different ways.

This section will touch on some of the various approaches to evaluation and highlight some differences between them. However, the focus of the module is to provide a practical guide for those with research experience, but perhaps limited exposure to evaluation. There are a myriad of evaluation handbooks and resources available on the internet sponsored by evaluation organizations, specific associations and individuals. Both the evaluation approaches used and the quality and usefulness of these resources vary significantly (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2004). While there are excellent resources (many of which offer the benefit of framing evaluation for a specific sector or issue); far too many evaluation guides offer formulistic approaches to evaluation – a template to guide the uninitiated.

This is not the approach taken here. Rather than provide a template that can be applied to any initiative, this module aims to provide the necessary background that will equip those with a research background to understand the concepts and alternatives related to evaluation, and to creatively apply these to a specific evaluation activity.

The similarities and differences between research and evaluation have long been the subject of intense debate: there are diverse and often conflicting perspectives (Levin-Rozalis, 2003). It is argued by some that evaluation and research are distinctly different. Proponents of this position cite such factors as the centrality of 'valuing' to evaluation; the inherently political nature of evaluation activities; the limited domain of application of evaluation findings (local and specific rather than transferable or generalizable); and the important role of theory in research compared to evaluation activities. It is also argued that the political and contextual framing of evaluation means that evaluators require a unique set of skills. Some describe evaluation as a profession, in contrast to research, where researchers belong to specific disciplines.

This sense of 'differentness' is reinforced by the fact that evaluators and researchers often inhabit very different worlds. Researchers are largely based in academic institutions and are most often engaged in research that is described as curiosity-driven. Many have no exposure to evaluation during their academic preparation. Evaluators (many of whom are not PhD prepared) are more likely to be working within the health system or established as consultants. In most cases, the two belong to different professional organizations, attend different conferences, and follow different (though overlapping) ethical guidelines.

Taking an alternative view are those who view evaluation as a form of research – using research methodology (and standards) to answer practical questions in a timely fashion. They argue that the commonly cited differences between evaluation and research do not apply to all forms of research, only to some of them. It is noted that the more engaged forms of research have many of the same characteristics and requirements as evaluation and similar skills are needed – skills in communication and collaboration, political astuteness, responsiveness to context, and ability to produce timely and useful findings. It is noted that the pragmatic use of diverse perspectives, disciplines and methods is not limited to evaluation, but applied by many researchers as well. Many evaluators stress the knowledge-generating aspects of evaluation (Preskill, 2008), and there is increasing interest in theory-driven evaluation (Coryn et al, 2010). This interest reflects increasing criticism of what is often called "black box" evaluation (the simple measurement of effects of interventions with little attention to how the effects are achieved). Findings from theory-driven evaluations can potentially be applied to other contexts – i.e. they are transferable. It is also argued that not all forms of evaluation are focused on determining value or worth; that there may be other purposes of evaluation. Many writers highlight the benefits of 'evaluative thinking' in planning and conducting research activities.

There are a number of reasons why researchers should be knowledgeable about evaluation:

The first reason is that the urgency of the problems facing the health system means that many new 'solutions' are being tried, and established processes and programs questioned.

Discussions with health care managers and executives highlight the reality that many of the 'research' questions they want addressed are, in reality, evaluation questions. They want to know whether a particular strategy is working, or will work, to address a known problem. They want accurate, credible, and timely information to inform decisions within the context in which they are working. Consequently, there is growing recognition of the need for evaluation expertise to guide decisions. Evaluation can address these needs and evaluation research, conducted by qualified evaluation researchers, can ensure the rigour of evaluation activities and optimize the potential that findings will be useful in other settings.

Research skills are required to ensure that such evaluations (which inform not only decisions about continuing or spreading an innovation, but also whether to discontinue current services, or change established processes) are well designed, implemented and interpreted. Poorly designed and overly simplistic evaluations can lead to flawed decision making – a situation that can be costly to all Canadians.

Many research proposals include some form of evaluation. For example, there are an increasing number of funding opportunities that result in researchers proposing 'pilot' programs to test new strategies. For these proposals, a rigorous evaluation plan is an essential component – one that will be discussed by the review panel. Results of this discussion are likely to influence the ranking of the proposal.

Researchers interested in knowledge translation theory and practice will also benefit from developing evaluation skills. Evaluation (particularly collaborative evaluation) brings the potential of promoting appropriate evidence use. Two of the often-stated frustrations of decision-makers are that a) there is often insufficient published research available to inform the challenges they are facing, and b) there is a need to incorporate contextual knowledge with research in order to inform local decisions. In turn, researchers often express concern that decision-makers are not familiar with research concepts and methods.

Early stages of well-designed and well-resourced evaluation research begin with a critical review and synthesis of the literature with local and contextual data. This can inform both evaluators and the program team on what is known about the issue, and about current leading practices. The process of designing an evaluation plan, guiding implementation of the evaluation, interpreting data, and making decisions on the data as the evaluation evolves can promote use of evidence throughout the planning/ implementation/ evaluation cycle. Even more importantly, a collaborative evaluation approach that incorporates key stakeholders in meaningful ways will help build evaluative thinking capacity, a culture that values evaluation and research literacy at the program/ organizational level. These skills can then be transferred to other organizational activities. An evaluation can be designed to provide some early results that may inform ongoing decision-making. And finally, because a collaboratively-designed evaluation reflects the questions of concern to decision-makers, evaluation can increase the likelihood that they will trust the evidence identified through the evaluation, and act in response to it.

It has been observed that "evaluation — more than any science — is what people say it is, and people currently are saying it is many different things" (Glass, 1980). This module will adopt the following definition, adapted from a commonly used definition of evaluation (Patton 1997, page 23):

The systematic collection of information about the activities, characteristics, and outcomes of program, services, policy, or processes, in order to make judgments about the program/process, improve effectiveness, and/or inform decisions about future development.

The definition, like many others, highlights the systematic nature of quality evaluation activities. For example Rossi et al., define evaluation as ". the use of social research methods to systematically investigate the effectiveness of social intervention programs" (2004, p. 28). It also highlights a number of other points that are often a source of misunderstandings and misconceptions about evaluation.

There are a number of common misconceptions about evaluation, misconceptions that have contributed to the limited use of evaluation by health researchers.

As the above definition illustrates, in addition to programs, evaluation can also focus on policy, products, processes or the functioning of whole organizations. Nor are evaluation findings limited to being useful to the particular program evaluated. While program evaluation activities are designed to inform program management decisions, evaluation research can generate knowledge potentially applicable to other settings.

The concept of 'valuing' is central to evaluation. In fact, some authors define evaluation in exactly these terms. Scriven, for example, defines evaluation as "the process of determining the merit, worth, or value of something, or the product of that process" (1991; p. 139).Data that is simply descriptive is not evaluation. (For example, "How many people participated in program X?" is not an evaluation question, although this data may be needed to answer an evaluation question). However, there are other purposes for undertaking an evaluation in addition to that of making a judgment about the value or worth of a program or activity (summative evaluation). Evaluation may also be used to refine or improve a program (often called formative evaluation) or to help support the design and development of a program or organization (developmental evaluation). Where there is limited knowledge on a specific topic, evaluation may also be used specifically to generate new knowledge. The appropriate selection of evaluation purpose is discussed in more detail in Section 2, Step 1.

This misconception is related to the previous one: if evaluation is only about judging the merit of an initiative, then it seems to make sense that this judgment should occur when the program is well established. The often-heard comment that it is 'too soon' to evaluate a program, reflects this misconception, with the result that evaluation – if it occurs at all - happens at the end of a program. Unfortunately, this often means that many opportunities have been missed to use evaluation to guide the development of a program (anticipate and prevent problems and make ongoing improvements), and to ensure that there is appropriate data collection to support end-of-project evaluation. It also contributes to the misconception that evaluation is all about outcomes.

In recent years, there has been an increasing emphasis on outcome, rather than process, evaluation. This is appropriate, as too often what is measured is what is easily measurable (e.g. services provided to patients) rather than what is important (e.g. did these services result in improvements to health?). The emphasis on outcome evaluation can, however, result in neglect of other forms of evaluation and even lead to premature attempts to measure outcomes. It is important to determine whether and when it is appropriate to measure outcomes in the activity you are evaluating. By measuring outcomes too early, one risks wasting resources and providing misleading information.

As this module will illustrate, much useful knowledge can be generated from an evaluation even if it is not appropriate or possible to measure outcomes at a particular point in time. In addition, even when an initiative is mature enough to measure outcomes, focusing only on outcomes may result in neglect of key program elements that need policy maker/program manager attention (Bonar Blalock, 1999). Sometimes what is just as (or more) important is understanding what factors contributed to the outcomes observed.

Some writers (and evaluation guides) identify only two purposes or 'types' of evaluation: summative and formative. Summative evaluation refers to judging the merit or worth of a program at the end of the program activities, and usually focuses on outcomes. In contrast, formative evaluation is intended as the basis for improvement and is typically conducted in the development or implementation stages of an initiative. Robert Stake is famously quoted on this topic as follows: "when the cook tastes the soup, that's formative; when the guests taste the soup, that's summative." However, as will be covered in later sections of this resource, the evaluation landscape is more nuanced and offers more potential than this simple dichotomy suggests. Section 2, Step 1, and Section 3, Step 8 provide more detail on evaluation alternatives.

A common misconception among many health care decision-makers is that evaluation is simply performance measurement. Performance measurement is primarily a planning and managerial tool, whereas evaluation research is a research tool (Bonar Blalock, 1999). Performance measurement focuses on results, most often measured by a limited set of quantitative indicators. This reliance on outcome measures and pre/ post measurement designs poses a number of risks, including that of attributing any observed change to the intervention under study without considering other influences; and failing to investigate important questions that cannot be addressed by quantitative measures. It also contributes to a common misperception that evaluation must rely only on quantitative measures.

Tending to rely on a narrow set of quantitative gross outcome measures accessible through Management Information Systems, performance management systems have been slow to recognize and address data validity, reliability, comparability, diversity, and analysis issues that can affect judgments of programs. Performance management systems usually do not seek to isolate the net impact of a program – that is, to distinguish between outcomes that can be attributed to the program rather than to other influences. Therefore, one cannot make trustworthy inferences about the nature of the relationship between program interventions and outcomes, or about the relative effects of variations in elements of a program's design, on the basis of performance monitoring alone (Bonar Blalock, 1999).

It is important to be aware of these common misconceptions as you proceed in developing an evaluation plan; not only to avoid falling into some of these traps yourself, but in order to prepare for conversations with colleagues and evaluation stakeholders, many of whom may come to the evaluation activity with such assumptions.

Evaluation can be described as being built on the dual foundations of a) accountability and control and b) systematic social inquiry (Alkin & Christie, 2004). For good reasons, governments (and other funders) have often emphasized the accountability functions of evaluation, which is one of the reasons for confusion between performance measurement and evaluation. Because the accountability focus usually leads to reliance on performance measurement approaches, a common result is a failure to investigate or collect data on the question of why the identified results occurred (Bonar Blalock, 1999).

There are dozens, even hundreds, of different approaches to evaluation (what some would call "philosophies", and others "theories"). Alkins and Christie (2004) describe an evaluation theory tree with three main branches: a) methods; b) valuing; and c) utilization. Some authors exemplifying these three 'branches' are Rossi (methods) (Rossi et al, 2004), Scriven (valuing) (Scriven, 1991), and Patton (utilization) (Patton, 1997). While some authors (and practitioners) may align themselves more closely with one of these traditions, these are not hard and fast categories – over time many evaluation theorists have incorporated approaches and concepts first proposed by others, and evaluation practitioners often take a pragmatic approach to evaluation design.

Each of these "branches" includes many specific evaluation approaches. It is beyond the scope of this module to review all of them here, but some examples are outlined below.

The methods tradition was originally dominated by quantitative methodologists. Over time, this has shifted, and greater value is now being given to incorporation of qualitative methods in evaluation within the methods theory branch.

The methods branch, with its emphasis on rigour, research design, and theory has historically been closest to research. Indeed, some of the recognized founders of the methods branch are also recognized for their work as researchers. The seminal paper "Experimental and Quasi-experimental Designs for Research" (Campbell and Stanley, 1966) has informed both the research and evaluation world. Theorists in this branch emphasize the importance of controlling bias and ensuring validity.

Of particular interest to researcher-evaluators is theory driven evaluation (Chen & Rossi, 1984). Theory-driven evaluation promotes and supports exploration of program theory – and the mechanisms behind any observed change. This helps promote theory generation and testing, and transferability of new knowledge to other contexts.

Theorists in this branch believe that what distinguishes evaluators from other researchers is that evaluators must place value on their findings – they make value judgments (Shadish et al., 1991). Michael Scriven is considered by many to be the primary mainstay of this branch: his view was that evaluation is about the 'science of valuing' (Alkins & Christie, 2004). Scriven felt that the greatest failure of an evaluator is to simply provide information to decision-makers without making a judgement (Scriven, 1983). Other theorists (e.g. Lincoln and Guba) also stress valuing, but rather than placing this responsibility on the evaluator, see the role of the evaluator as helping facilitate negotiation among key stakeholders as they assign value (Guba & Lincoln, 1989).

In contrast to those promoting theory-driven evaluation, those in the valuing branch may downplay the importance of understanding why a program works, as this is not always seen as necessary to determining its value.

The centrality of valuing to evaluation may present challenges to researchers from many disciplines, who often deliberately avoid making recommendations; cautiously remind users of additional research needed; and believe that 'the facts should speak for themselves'. However, with increasing demands for more policy and practice relevant research, many researchers are grappling with their role in providing direction as to the relevance and use of their findings.

A number of approaches to evaluation (see for example Patton, Stufflebeam, Cousins, Pawley, add others), have a "utilization" focused orientation. This branch began with what are often referred to as decision-oriented theories (Alkin & Christie, 2004), developed specifically to assist stakeholders in program decision-making. This branch is exemplified by, but not limited to, the work of Michael Q. Patton (author of Utilization-focused evaluation (1997)). Many collaborative approaches to evaluation incorporate principles of utilization-focused evaluation.

The starting point for utilization approaches is the realization that, like the results of research, many evaluation reports end up sitting on the shelf rather than being acted on – even when the evaluation has been commissioned by one or more stakeholders. With this in mind, approaches that emphasize utilization incorporate strategies to promote appropriate action on findings. They emphasize the importance of early and meaningful collaboration with key stakeholders and build in strategies to promote 'buy in' and use of evaluation findings.

Authors closer to the utilization branch of evaluation find much in common with knowledge translation theorists and practitioners: in fact, the similarities in principle and approach between integrated knowledge translation (iKT) 2 and utilization-focused evaluation (UFE) are striking.

Both iKT and UFE:

While it is helpful to have knowledge of the different roots of, and various approaches to, evaluation, it is also important to be aware that there are many common threads in these diverse evaluation approaches (Shadish, 2006) and that evaluation societies have established agreement on key evaluation principles.

The previous section provided a brief overview of evaluation concepts. This section is the first of two that will provide a step-by-step guide to preparing for and developing an evaluation plan. Both sections will provide additional information particularly helpful to those who are conducting collaborative evaluations or have partners outside of academia.

While the activities outlined in this section are presented sequentially, you will likely find that that the activities of a) considering the evaluation purpose, b) identifying stakeholders, c) assessing evaluation expertise, d) gathering relevant evidence, and e) building consensus are iterative. Depending on the evaluation, you may work through these tasks in a different order.

One of the first steps in planning evaluation activities is to determine the purpose of the evaluation. It is possible, or even likely, that the purpose of the evaluation may change – sometimes significantly – as you undertake other preparatory activities (e.g. engaging stakeholders, gathering additional information). For this reason, the purpose is best finalized in collaboration with key stakeholders. However, as an evaluator, you need to be aware of the potential purposes of the evaluation and be prepared to explore various alternatives.

As indicated earlier, there are four broad purposes for conducting an evaluation:

This is the form of evaluation (summative evaluation) most people are familiar with. It is appropriate when a program is well established, and decisions need to be made about its impacts, continuation or spread.

Many researchers are involved in pilot studies (small studies to determine the feasibility, safety, usefulness or impacts of an intervention before it is implemented more broadly). The purpose of these studies is to determine whether there is enough merit in an initiative to develop it further, adopt it as is, or to expand it to other locations. Pilot studies, therefore, require some level of summative evaluation – there is a need to make a judgment about one or more of these factors. What is often overlooked, however, is that an evaluation of a pilot study can do more than assess merit – in other words, it can have more than this one purpose. A well-designed evaluation of a pilot can also identify areas for program improvement, or explore issues related to implementation, cost effectiveness, or scaling up the intervention. It may even identify different strategies to achieve the objective of the pilot.

If a program is still 'getting up and running' it is too soon for summative evaluation. In such cases, evaluation can be used to help guide development of the initiative (formative evaluation). However, an improvement-oriented approach can also be used to assess an established intervention. A well-designed evaluation conducted for the purpose of program improvement can provide much of the same information as a summative evaluation (e.g. information as to what extent the program is achieving its goals). The main difference is that the purpose is to help improve, rather than to make a summative judgment. For example, program staff often express the wish to evaluate their programs in order to ensure that they are doing the 'best possible job' they can. Their intent (purpose) is to make program improvements. One advantage of improvement-oriented evaluation is that, compared to summative evaluation, it tends to be less threatening to participants and more likely to promote joint problem-solving.

Developmental evaluation uses evaluation processes, including asking evaluative questions and applying evaluation logic, to support program, product, staff and/or organizational development. Reflecting the principles of complexity theory, it is used to support an ongoing process of innovation. A developmental approach also assumes that the measures and monitoring mechanisms used in the evaluation will continue to evolve with the program. A strong emphasis is placed on the ability to interpret data emerging from the evaluation process (Patton, 2006).

In developmental evaluation, the primary role of the evaluator, who participates as a team member rather than an outside agent, is to develop evaluative thinking. There is collaboration among those involved in program design and delivery to conceptualize, design and test new approaches in a long-term, on-going process of continual improvement, adaptation and intentional change. Development, implementation and evaluation are seen as integrated activities that continually inform each other.

In many ways developmental evaluation appears similar to improvement-oriented evaluation. However, in improvement-oriented evaluation, a particular intervention (or model) has been selected: the purpose of evaluation is to make this model better. In developmental evaluation, in contrast, there is openness to other alternatives – even to changing the intervention in response to identified conditions. In other words, the emphasis is not on the model (whether this is a program, a product or a process), but the intended objectives of the intervention. A team may consider an intervention, evaluated as 'ineffective', a success if thoughtful analysis of the intervention provides greater insights and direction to a more informed solution.

Developmental evaluation is appropriate when there is a need to support innovation and development in evolving, complex, and uncertain environments (Patton, 2011; Gamble 2006). While considered by many a new (and potentially trendy) evaluation strategy, it is not appropriate in all situations. First, evaluation of straightforward interventions usually will not require this approach (e.g. evaluation of the implementation of an intervention found effective in other settings). Second, there must be an openness to innovation and flexibility of approach by both the evaluation sponsor and the evaluators. Third, it requires an ongoing relationship between the evaluator and the initiative to be evaluated.

A final purpose of evaluation is to create new knowledge – evaluation research. Often, when there is a request to evaluate a program, a critical review of the literature will reveal that very little is known about the issue or intervention to be evaluated. In such cases, evaluators may design the evaluation with the specific intent of generating knowledge that will potentially be applicable in other settings – or provide more knowledge about a specific aspect of the intervention.

While it is unusual that evaluation would be designed solely for this purpose (in most cases such an endeavor would be defined as a research project), it is important for researchers to be aware that appropriately-designed evaluation activities can contribute to the research literature.

As can be seen from the potential evaluation questions listed below, an evaluation may develop in very different ways depending on its purpose.

In our case study example, a provincial department of health was originally looking for a summative evaluation (i.e. they wanted to know which model was 'best'). There was an implication (whether or not explicitly stated) that results would inform funding and policy decisions (e.g. implementation of the 'best' model in all funded hospitals).

However, in this case preliminary activities determined that:

There was also concern that the focus on 'models of care' may avoid consideration of larger system issues believed to be affecting the concerns the models were intended to address, and little confidence that the evaluation would consider all the information the different programs felt was important.

As a result, the evaluators suggested that the purpose of the evaluation be improvement oriented (looking for ways each of the models could be improved) rather than summative. This recommendation was accepted, with the result that evaluators were more easily able to gain the support and participation of program staff in a politically-charged environment. By also recognizing the need to generate knowledge in an area where little was at that time known, the evaluators were able to design the evaluation to maximize the generation of knowledge. In the end, the evaluation also included an explicit research component, supported by research funding.

While an evaluation may achieve more than one purpose, it is important to be clear about the main intent(s) of the activity. As the above discussion indicates, the purpose of an evaluation may evolve during the preparatory phases.

The concept of intended users (often called 'key' or 'primary' stakeholders) is an important one in evaluation. It is consistent with that of 'knowledge user' in knowledge translation. In planning an evaluation it is important to distinguish intended users (those you are hoping will take action on the results of the evaluation) from stakeholders (interested and affected parties) in general. Interested and affected parties are those who care about, or will be affected by the issue and your evaluation results. In health care, these are often patients and families, or sometimes staff. Entire communities may also be affected. However, depending on the questions addressed in the evaluation, not all interested or affected parties will be in a position to act on findings. For example, the users of an evaluation of a new service are less likely to be patients (as much as we may believe they should be) than they are to be senior managers and funders.

The experiences and preferences of interested and affected parties need to be incorporated into the evaluation if the evaluation is to be credible. However, these parties are often not the primary audience for evaluation findings. They may be appropriately involved by ensuring (for example) that there is incorporation of a systematic assessment of patient/ family or provider experience in the evaluation. However, depending on the initiative, these patients or staff may – or may not – be the individuals who must act on evaluation findings. The intended audience (those who need to act on the findings) may not be staff – but rather a senior executive or a provincial funder.

It is important to keep in mind the benefits of including, in meaningful ways, the intended users of an evaluation from the early stages. As we know from the literature, a key strategy for bridging the gap between research and practice is to build commitment to (and 'ownership of') the evaluation findings by those in a position to act on them (Cargo & Mercer, 2008). This does not mean that these individuals need to be involved in all aspects of the research (e.g. data collection) but that, at a minimum, they are involved in determining the evaluation questions and interpreting the data. Many evaluators find that the best strategy for ensuring this is to create a steering/ planning group to guide the evaluation – and to design it in such a way as to ensure that all key stakeholders can, and will, participate.

Funders (or future funders) can be among the most important audiences for an evaluation. This is because they will be making the decision as to whether to fund continuation of the initiative. Take, for example, a pilot or demonstration project that is research-funded. It may not be that difficult to obtain support from a health manager (or senior management of a health region) to provide the site for a pilot program of an innovation if the required funding comes from a research grant. If, however, it is hoped that a positive evaluation will result in adoption of the initiative on an ongoing basis, it is wise to ensure that those in a position to make such a decision are integrally involved in design of the evaluation of the pilot, and that the questions addressed in the evaluation are of interest and importance to them.

Once key stakeholders have been identified, evaluators are faced with the practical task of creating a structure and process to support the collaboration. If at all possible, try to find an existing group (or groups) that can take on this role. Because people are always busy, it may be easier to add a steering committee function to existing activities.

In other cases, there may be a need to create a new body, particularly if there are diverse groups and perspectives. Creating a neutral steering body (and officially recognizing the role and importance of each stakeholder by inviting them to participate on it) may be the best strategy in such cases. Whatever structure is selected, be respectful of the time you ask from the stakeholders – use their time wisely.

Another important strategy, as you develop your evaluation plan, is to build in costs of stakeholders. These costs vary depending on whether stakeholders are from grassroots communities or larger health/ social systems. What must be kept in mind is that key stakeholders (intended evaluation users), like knowledge users in research, do not want to simply be used as 'data sources'. If they are going to put their time into the evaluation they need to know that they will be respected partners, their expertise will be recognized, and that there will be benefit to their organization. A general principle is that the 'costs' of all parties who are contributing to the evaluation should be recognized – and as much as possible – compensated for. This compensation may not always need to be financial. Respect and valuing can also be demonstrated through:

If key stakeholders are direct care staff in the health system, it will be difficult to ensure their participation unless the costs of 'back-filling' their functions are provided to the organization. Similarly, physicians in non-administrative positions may expect compensation due to lost income.

You may be wondering about the time it will take to set up such a committee, maintain communication, and attend meetings. This does take time, but it is time well spent as it will:

It is particularly important to have a steering committee structure if you are working in a culture new to you (whether this is an organizational culture, an ethno-cultural community, or in a field or on an issue with which you are unfamiliar). Ensuring that those with needed cultural insights are part of the steering/ planning committee is one way of facilitating an evaluation that is culturally 'competent' and recognizes the sensitivities of working in a specific context.

It may not be feasible to have all those on a collaborative committee attend at the same time, particularly if you are including individuals in senior positions. It may not even be appropriate to include all intended users of the evaluation (e.g. funders) with other stakeholders. However, all those that you hope will take an interest in evaluation findings and act on the results need to be included in a minimum of three ways:

It is also essential that the lead evaluators are part of this steering committee structure, although – depending on your team make-up (Step 4) – it may not be necessary to have all those supporting the evaluation attend every meeting.

A key challenge is to ensure that you have the evaluation expertise needed on your team:

A common mistake of researchers is to assume that their existing research team has the required evaluation skills. Sometimes assessment of this team by the review panel will reveal either limited evaluation expertise, or a lack of specific evaluation skills needed for the proposed evaluation plan. For example, an evaluation plan that relies on assessment of staff/ patient perspectives of an innovation will require a qualitative researcher on the research team. Remember that there is a need for knowledge and experience of the 'culture' in which the evaluation takes place, as well as generic skills of communication, political astuteness and negotiation. Ensuring that you have, on the team, all the expertise that is needed for the particular evaluation you are proposing, will strengthen your proposal. Do not rely simply on contracting with an evaluation consultant who has not been involved to date.

Reviewing your evaluation team composition is an iterative activity – as the evaluation plan develops, you may find a need to add evaluation questions (and consequently expand the methods employed). This may require review of your existing expertise.

The evaluation literature frequently distinguishes between "internal" and "external" evaluators. Internal evaluators are those who are already working with the initiative – whether health system staff or researchers. External evaluators do not have a relationship with the initiative to be evaluated. It is commonly suggested that use of internal evaluators is appropriate for formative evaluation, and external evaluation is required for summative evaluation.

The following table summarizes commonly identified differences between internal and external evaluation.

This dichotomy, however, is too simplistic for the realities of many evaluations, and does not – in itself - ensure that the evaluation principles of competence and integrity are met. Nor does it recognize that there may be other, more creative solutions than this internal/ external dichotomy suggests. Three potential strategies, with the aims of gaining the advantages of both internal and external evaluation, are elaborated in more detail below:

A collaborative approach, where evaluators participate with stakeholders as team members. This is standard practice in many collaborative evaluation approaches, and a required element of a utilization-focused or developmental evaluation. Some evaluators differentiate between objectivity in evaluation (which implies some level of indifference to the results) and neutrality (meaning that the evaluator does not 'take sides') (Patton, 1997). Collaborative approaches are becoming more common, reflecting awareness of the benefits of collaborative research and evaluation.

Identifying specific evaluation components requiring external expertise (whether for credibility or for skill), and incorporation of both internal and external evaluators into the evaluation plan. Elements of an evaluation that require external evaluation (whether formative or summative) are those:

Activities that may be well suited to evaluation by those internal to the initiative are those where there are the resources in skill and time to conduct them, and participation of internal staff will not affect evaluation credibility. One example might be the collection and collation of descriptive program data. In some situations it may be appropriate to contract with a statistical consultant for specialized expertise, while using staff data analysts to actually produce the data reports.

Use of internal expertise that is at 'arms length' from the specific initiative. A classic example of this would be contracting with an organization's internal research and evaluation unit to conduct the evaluation (or components of it). While this is not often considered an external evaluation (and may not be the optimal solution in situations where the evaluation is highly politicized), it often brings together a useful combination of:

The program, product, service, policy or process you will be evaluating exists in a particular context. Understanding context is critical for most evaluation activities: it is necessary to undertake some pre-evaluation work to determine the history of the initiative, who is affected by it, perspectives and concerns of key stakeholders, and the larger context in which the initiative is situated (e.g. the organizational and policy context). How did the initiative come to be? Has it undergone previous evaluation? Who is promoting evaluation at this point in time and why?

In addition, a literature review of the issue(s) under study is usually required before beginning an evaluation. Identifying, accessing and using evidence to apply to an evaluation is an important contribution of research. Such a review may focus on:

If an evaluation is potentially contentious, it is also often a good idea to meet individually with each of the stakeholders, in order to promote frank sharing of their perspectives.

The first step in this evaluation was to undertake a literature review. While it was hoped that a systematic review would provide some guidance as a recommended model, this was not the case – almost no literature on the topic addressed issues related to the specific context. Presentation of this finding at a meeting of stakeholders also indicated that there were a number of tensions and diverse perspectives among stakeholders.

One of the next steps proposed by the evaluators was to make a site visit to each of the sites. This included a walk-through of the programs, and meetings with nursing and physician leadership. These tours accomplished two things: a) additional information on 'how things worked' that would have been difficult to gage through other means, and b) development of rapport with staff – who appreciated having input into the evaluation and describing the larger context in which the services were offered.

A review of the research literature identified a) key principles predicting effective adoption, b) the importance of implementation activities, and c) limited information on the impacts of computerized decision-support in this specific medical area. This knowledge provided additional support for the decision to a) focus on implementation evaluation, and b) expand the original plan of pre/post intervention measurement of test ordered to include a qualitative component that explored user perspectives.

As indicated in earlier sections, evaluation is subject to a number of misconceptions, and may have diverse purposes and approaches. It is usually safe to assume that not all stakeholders will have the same understanding of what evaluation is, or the best way to conduct an evaluation on the issue under consideration. Some are likely to have anxieties or concerns about the evaluation.

For this reason, it is important to build shared understanding and agreement before beginning the evaluation. Many evaluators find that it is useful to build into the planning an introductory session that covers the following:

This overview can take as little as 20 minutes if necessary. It allows the evaluator to proactively address many potential misconceptions – misconceptions that could present obstacles both to a) support of and participation in the evaluation and to b) interest in acting on evaluation findings. Additional benefits of this approach include the opportunity to build capacity among evaluation stakeholders, and to begin to establish an environment conducive to collaborative problem-solving.

It is also important to ensure that the parameters of the evaluation are well defined. Often, the various stakeholders involved in the evaluation process will have different ideas of where the evaluable entity begins and ends. Reaching consensus on this at the outset helps to set clear evaluation objectives and to manage stakeholder expectations. This initial consensus will also help you and your partners keep the evaluation realistic in scope as you develop an evaluation plan. Strategies for focusing an evaluation and prioritizing evaluation questions are discussed in Steps 8 and 9.

In this example, the introductory overview on evaluation was integrated with the site visits. Key themes were reiterated in the initial evaluation proposal, which was shared with all sites for input. As a result, even though staff from the three institutions had not met together, they developed a shared understanding of the evaluation and agreement on how it would be conducted.

You may find that consensus-building activities fit well into an initial meeting of your evaluation partners. In other cases, such discussions may be more appropriate once all stakeholders have been identified.

In collaborative evaluation with external organizations, it is also important to clarify roles and expectations of researchers and program staff/ managers, and make explicit any in-kind time commitments or requirements for data access. It is particularly important to have a clear agreement on data access, management and sharing (including specifics of when and where each partner will have access) before the evaluation begins.

Before embarking on the evaluation it is also important to clarify what information will be made public by the evaluator. Stakeholders need to know that results of research-funded evaluations will be publicly reported. Similarly, staff need to know that senior executives will have the right to see the results of program evaluations funded by the sponsoring organization.

It is also important to proactively address issues related to 'speaking to' evaluation findings. It is not unknown that a sponsoring organization may – in fear that an evaluation report will not be what it hoped for – choose to present an early (and more positive) version of findings before the final report is released. In some cases, they may not want results shared. For this reason it is important to be clear about roles, and to clarify that the evaluator is the person who is authorized to speak to accurately reflect the findings, accept speaking invitations or publish on the results of the evaluation. (Developing and presenting results in collaboration with stakeholders is even better.) Similarly, it is for the program/ organization leads to speak to the specific issues related to program design.

Research proposals that include evaluative components are strengthened by clear letters of commitment from research and evaluation partners. These letters should specifically outline the nature and extent of partners in developing the proposal; the structure and processes for supporting collaborative activities; and the commitments and contributions of partners to the proposed evaluation activities (e.g. data access; provision of in-kind services).

Special Note: While this activity is placed in the preparation section of this guide, many evaluators find that, in practice, getting a clear description of the program, and the mechanism of action through which it is expected to work, may not be a simple activity. It is often necessary to delay this activity until later in the planning process, as you may need the active engagement of key stakeholders in order to facilitate what is often a challenging task.

Having stakeholders describe the program is useful for a number of reasons:

However, you may find that those involved in program management find the process of describing their program or initiative on paper a daunting task. An important role of the evaluator may be to help facilitate this activity.

One deliverable requested by the provincial health department was a description of how each of the different models worked. This early activity took over 6 months: each time a draft was circulated for review, stakeholders identified additional information and differences of opinion about how things actually worked in practice.

Many evaluators place a strong emphasis on logic models. Logic models visually illustrate the logical chain of connections showing what the intervention is intended to accomplish. In this way, a logic model is consistent with theory-driven evaluation, as the intent is to get inside the "black box", and articulate program theory. Researchers will be more familiar with 'conceptual' models or frameworks, and there are many similarities between the two. However, a conceptual framework is generally more theoretically-based and conceptual than a logic model, which tends to be program specific and include more details on program activities.

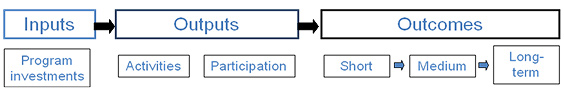

When done well, logic models illustrate the 'if-then' and causal connections between program components and outcomes, and can link program planning, implementation and evaluation. They can be of great benefit in promoting clear thinking, and articulating program theory. There are many different formats for logic models ranging from simple linear constructions to complex, multidimensional representations. The simplest show a logical chain of connections under the headings of inputs (what is invested in the initiative), outputs (the activities and participants), and the outcomes (short, medium and long-term).

Other logic models are more complex, illustrating complex, multi-directional relationships. See, for example, various templates developed by the University of Wisconsin.

In spite of the popularity of logic models, they do have potential limitations, and they are not the only strategy for promoting clarity on the theory behind the intervention to be evaluated.

Too often, logic models are viewed as a bureaucratic necessity (e.g. a funder requirement) and the focus becomes one of "filling in the boxes" rather than articulating the program theory and the evidence for assumptions in the program model. In other words, rather than promoting evaluative thinking, the activity of completing a logic model can inhibit it. Another potential downside is that logic models tend to be based on assumptions of linear, logical relationships between program components and outcomes that do not reflect the complexity in which many interventions take place. Sometimes logic models can even promote simplistic (in the box) thinking. Some authors advise that logic models are not appropriate for evaluations within complex environments (Patton, 2011).

Whether or not a graphic logic model is employed as a tool to aid in evaluation planning, it is important to be able to articulate the program theory: the mechanisms through which change is anticipated to occur. A program description, advised above, is one first step to achieving this. Theory can sometimes be effectively communicated through a textual approach outlining the relationships between each component of the program/ process. (Because there is strong evidence on X, we have designed intervention Y). This approach also brings the benefit of a structure that facilitates inclusion of available evidence for the proposed theory of action.

While presented in a step-wise fashion, activities described in this section are likely to be undertaken concurrently. Information gathered through each of the activities will inform (and often suggest a need to revisit) other steps. It is important to ensure that these preliminary activities have been addressed before moving into development of the actual evaluation plan.

The steps outlined in this section can come together very quickly if the preparatory work advised in Section 2 has been completed. These planning activities are ideally conducted in collaboration with your steering/ planning group.

For these next steps, the module will be based on an evaluation planning matrix (Appendix A). This matrix is not meant to be an evaluation template, but rather a tool to help organize your planning. Caution is needed in using templates in evaluation, as evaluation research is much more than a technical activity. It is one that requires critical thinking, assessment of evidence, careful analysis and clear conceptualization.

The first page of the matrix provides a simple outline for documenting a) the background of the initiative, b) the purpose of the planned evaluation, c) the intended use of the evaluation, d) the key stakeholders (intended evaluation users), e) and the evaluation focus. Completion of preparatory activities should allow you to complete sections a-d.

This section will start with a discussion of focus (Step 8, below), and then lead through the steps of completing page 2 of the matrix (Steps 9-11). Appendix B provides a simple example of the completed matrix for Case Study 1: Unassigned Patients.

Through the preparatory activities you have been clarifying the overall purpose of the evaluation. At this point, it is useful to operationalize the purpose of evaluation by developing a clear, succinct description of the purpose for conducting this particular evaluation. This purpose statement, one to two paragraphs in length, should guide your planning.

It is also important to include a clear statement of how you see the evaluation being used (this should be based on the preparatory meetings with stakeholders), and who the intended users of the evaluation are.

Renegotiation of the purpose of the evaluation of hospital models of care resulted in an evaluation purpose that was described as follows:

In keeping with an improvement-oriented evaluation approach, there is no intent to select one 'best model', but rather to identify strengths and limitations of each strategy with the objective of assisting in improving quality of all service models.

Preliminary consultation has also identified three key issues requiring additional research: a) understanding and improving continuity of patient care; b) incorporating provider and patient/ family insights into addressing organizational barriers to effective provision of quality inpatient care and timely discharge; and c) the impact of different perspectives of various stakeholders on the effectiveness of strategies for providing this care.

This evaluation will be used by staff of the department of health to inform decisions about continued funding of the programs; by site senior management to strengthen their specific services; and by regional senior management to guide ongoing planning.

This evaluation summarized its purpose as follows:

The purpose of this evaluation research is to identify facilitators and barriers to implementation of decision-support systems in the Canadian health context; to determine the impacts of introduction of the decision-support system; and to develop recommendations to inform any expansion or replication of such a project. It is also anticipated that findings from this evaluation will guide further research.

As these examples illustrate, it is often feasible to address more than one purpose in an evaluation. The critical point is, however, to be clear about the purpose, the intended users of the evaluation, and the approach proposed for working with stakeholders.

So far, we have discussed the purpose of the evaluation, and, in broad terms, some of the possible approaches to evaluation. Another concept that is critical to evaluation planning is that of focus. Whatever the purpose, an evaluation can have any one of dozens of foci (For example Patton (1997) lists over 50 potential foci). These include:

Through exploring the experience and perspectives of all stakeholders, the evaluation found that those receiving the computerized orders, while finding them easier to read (legibility was no longer a problem) also found that they contained less useful information due to the closed-ended drop down boxes which replaced open-ended physician description of the presenting problem. This question was not one that had been identified as an objective, but had important implications for future planning.

It is also important to sequence evaluation activities – the focus you select will depend at least in part on the stage of development of the initiative you are evaluating. A new program, which is in the process of being implemented, is not appropriate for outcome evaluation. Rather, with few exceptions, it is likely that the focus should be on implementation evaluation. Implementation evaluation addresses such questions as:

A program that has been implemented and running for some time, may select a number of different foci for an improvement-oriented evaluation.

Many summative (judgment-oriented) evaluations are likely to take a focus that is impact or outcome focused.

It is important to keep in mind that a focus will help keep parameters on your activities. The potential scope of any evaluation is usually much broader than the resources available. This, in addition to the need to sequence evaluation activities, makes it useful to define your focus.

Only when preparatory activities have been completed is it time to move on to identifying the evaluation questions. This is not to say that a draft of evaluation questions may not have already been developed. If only the research team is involved, questions may already be clearly defined: if you have been commissioned to undertake an evaluation, at least some of the evaluation questions may be predetermined. However, if you have been meeting with different stakeholders, they are likely to have identified questions of concern to them. The process of developing the evaluation questions is a crucial one, as they form the framework for the evaluation plan.

At this point we move on to page 2 of the evaluation planning matrix. It is critical to 'start with the question'; i.e. with what we want to learn from the evaluation. Too often, stakeholders can become detracted by first focusing on the evaluation activities they would like to conduct (e.g. We should conduct interviews with physicians), the data they think is available (e.g. We can analyze data on X), or even the indicators that may be available. But without knowing what questions the evaluation is intended to answer, it is premature to discuss methods or data sources.

In working with evaluation stakeholders, it is often more useful to solicit evaluation questions with wording such as "what do you hope to know at the end of this evaluation that you don't know now?" ratherthan as "what are the evaluation questions?" The latter question is more likely to elicit specific questions for an interview, focus group, or data query, than to identify questions at the level you will find helpful.

If you are conducting a collaborative evaluation, a useful strategy is to incorporate a discussion (such as a brainstorming session) with your stakeholder group. You will often find that, if there is good participation, dozens of evaluation questions may be generated – often broad in scope, and at many different levels. Scope of questions can often be constrained if there is a clear consensus on the purpose and focus on the evaluation – the reason that leading the group through such a discussion (Section 2, Step 6) is useful.

The next step for the evaluator is to help the group rework these questions into a format that is manageable. This usually involves a) 'rolling up' the questions into overarching questions, and b) being prepared to give guidance as to sequence of questions. These two activities will facilitate the necessary task of prioritizing the questions: reaching consensus on which are of most importance.

Many questions that are generated by knowledge users are often subquestions of a larger question. The task of the evaluator is to facilitate the roll-up of questions into these overarching ones. Because it is important to demonstrate to participants that the questions of concern to them are not lost, it is often useful to keep note (in column two of the matrix) of all the questions of concern.

The stakeholders at the 3 sites generated a number of questions, many of which were similar. For example: "I want to know what nurses think about this model", "I want to know about the opinions of patients on this change", "How open are physicians to changes to the model?'

These questions could be summarized in an overarching question "What are the perspectives of, and experiences with, physicians, nurses, patients, families, and other hospital staff" on the care model?"

It is common for knowledge users (and researchers) to focus on outcome-related questions. Sometimes it is possible to include these questions in the evaluation you are conducting, but in many cases – particularly if you are in the process of implementing an initiative – it is not. As discussed earlier, for example, it is not appropriate to evaluate outcomes until you are sure that an initiative has been fully implemented. In other cases, the outcomes of interest to knowledge users will not be evident until several years into the future – although it may be feasible to measure intermediate outcomes.

However, even if it is not possible to address an outcome evaluation question in your evaluation it is important to take note of these desired outcomes. First, this will aid in the development of program theory and, secondly, noting the desired outcome measures is an essential first step in ensuring that there are adequate and appropriate data collection systems in place that will facilitate outcome evaluation in the future.

If it is not possible to address outcome questions, be sure to clearly communicate that these are important questions that will be addressed at a more appropriate point in the evaluation process.

Even when the evaluation questions have been combined and sequenced, there are often many more questions of interest to knowledge users than there is time (or resources) to answer them. The role of the evaluator at this point is to lead discussion to agreement on the priority questions. Some strategies for facilitating this include:

If there is time, the steering/planning group can participate in this 'rolling up' and prioritization activity. Another alternative is for the evaluator to develop a draft based on the ideas generated and to circulate it for further input.

It is only when the evaluation questions have been determined that it is appropriate to move on to the next steps: evaluation design, selection of methods and data sources, and identification of indicators.

Only when you are clear on the questions, and have prioritized them, is it time to select methods. In collaborative undertakings you may find that strong facilitation is needed to reach consensus on the questions, as stakeholders are often eager to move ahead to discussion of methods. The approach of 'starting with the question' may also be a challenge for researchers, who are often highly trained in specific methodologies and methods. It is important in evaluation, however, that methods be driven by the overall evaluation questions, rather than by researcher expertise.

Evaluators often find that many evaluations require a multi-method approach. Some well-designed research and evaluation projects can generate important new knowledge using only quantitative methods. However, in many evaluations it is important to understand not only if an intervention worked (and to measure accurately any difference it made) but to understand why the intervention worked – the principles or characteristics associated with success or failure, and the pathways through which effects are generated. The purpose of evaluating many pilot programs is to determine whether the program should be implemented in other contexts, not simply whether it worked in the environment in which it was evaluated. These questions generally require the addition of qualitative methods.

Your steering committee will also be helpful at this stage, as they will be able to advise you on the feasibility – and credibility - of certain methods.

When the request for the evaluation was made, it was assumed that analysis of administrative data would be the major data source for answering evaluation questions. In fact, the data available was only able to provide partial insights to some of the questions of concern.

While the overall plan for the evaluation suggested focus groups would be appropriate for some data collection, the steering group highlighted the challenges in bringing physicians and hospital staff together as a group. They were, however, able to suggest strategies to facilitate group discussions, (integrating discussions with staff meetings, planning a catered lunch, and individualized invitations from respected physician leaders).

The process of identifying data sources is often interwoven with that of selecting methods. For example, if quantitative program data are not available to inform a specific evaluation question, there may be a need to select qualitative methods. In planning a research project, if the needed data were not available, a researcher may decide to remove a particular question from the study. In evaluation, this is rarely acceptable – if the question is important, there should be an effort to begin to answer it. As Patton (1997) has observed, it is often better to get a vague or fuzzy answer to an important question than a precise answer to a question no one cares much about. The best data sources in many cases are specific individuals!

Remember that many organizations have formal approval processes that must be followed before you can have access to program data, staff or internal reports.

Once evaluation questions have been identified, and methods and data sources selected, it is time to explore what indicators may be useful.

An indicator can be defined as a summary statistic used to give an indication of a construct that cannot be measured directly. For example, we cannot directly measure the quality of care, but we can measure particular processes (e.g., adherence to best-practice guidelines) or outcomes (e.g., number of falls) thought to be related to quality of care. Good indicators:

. should actually measure what they are intended to (validity); they should provide the same answer if measured by different people in similar circumstances (reliability); they should be able to measure change (sensitivity); and, they should reflect changes only in the situation concerned (specificity). In reality, these criteria are difficult to achieve, and indicators, at best, are indirect or partial measures of a complex situation (Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (1998: 5).

However, it is easy to overlook the limitations both of particular indicators and of indicators in general. Some authors have observed that the statement "we need a program evaluation" is often immediately followed by "we have these indicators," without consideration of exactly which question the indicators will answer (Bowen & Kriendler, 2008).

An exclusive focus on indicators can lead to decisions being data-driven rather than evidence-informed (Bowen et al. 2009). It is easy to respond to issues for which indicators are readily available, while ignoring potentially more important issues for which such data is not available. Developing activities around "what existing data can tell us," while a reasonable course for researchers, can be a dangerous road for both decision-makers and evaluators, who may lose sight of the most important questions facing the healthcare system. It has been observed that "the indicator-driven approach 'puts the cart before the horse' and often fails" (Chesson 2002: 2).

Not all indicators are created equal, and an indicator's limitations may not be obvious. Many indicators are 'gameable' (i.e. metrics can be improved without substantive change). For example, breastfeeding initiation is often used as an indicator of child health, as it is more easily measured than breastfeeding duration. However, lack of clear coding guidelines, combined with pressure on facilities to increase breastfeeding rates, appear to have produced a definition of initiation as, "the mother opened her gown and tried" (Bowen & Kriendler, 2008). It is not surprising then that hospitals are able to dramatically increase 'breastfeeding rates' if a directive is given to patient care staff, who are then evaluated on the results. This attempt, however, does not necessarily increase breastfeeding rates following hospital discharge. This example also demonstrates that reliance on a poor indicator can result in decreased attention and resources for an issue that may continue to be of concern.

The following advice is offered to avoid these pitfalls in indicator use in evaluation:

At the beginning of this evaluation it was assumed that assessment of impact would be fairly straightforward: the proposed indicator for analysis was hospital length of stay (LOS). However, discussions with staff at one centre uncovered that:

At this point, we are ready to move the evaluation plan into operation. It is necessary to ensure that you have the resources to conduct the proposed evaluation activities, and know who is responsible for conducting them. This final column in the matrix provides the base from which an evaluation workplan can develop.

This module does not attempt to provide detailed information on project implementation and management, although some resources to support this work (e.g. checklists) are included in the bibliography. However, as you conduct the evaluation it is important to:

Even though it is recommended that there are regular reports (and opportunities for discussion) as the evaluation progresses, it is often important to leave a detailed evaluation report. This report should be focused to the intended users of the evaluation, and should form the basis of any presentations or academic publications, helping promote consistency if there are multiple authors or presenters.

Evaluation frequently faces the challenge of communicating contentious or negative findings. Issues related to communication are covered in more detail in Section 4, Ethics and Evaluation.

There are many guidelines for developing reports for knowledge users. The specifics will depend on your audience, the scope of the evaluation and many other factors. A good starting point is the CFHI resources providing guidance in communicating with decision-makers.

Evaluation societies have clearly identified ethical standards of practice. The Canadian Evaluation Society (n.d) provides Guidelines for Ethical Conduct, (competence, integrity, accountability) while the American Evaluation society (2004) publishes Guiding principles for evaluators (systematic inquiry, competence, integrity/honesty, respect for people, and responsibilities for general and public welfare).

The ethics of evaluation are an important topic in evaluation journals and evaluation conferences. Ethical behavior is a 'live issue' among professional evaluators. This may not be apparent to researchers as, in many jurisdictions, evaluation is exempt from the ethical review processes required by universities.

In addition to the standards and principles adopted by evaluation societies, it is important to consider the ethical issues specific to the type of evaluation you are conducting. For example there are a number of ethical issues related to collaborative and action research or undertaking organizational research (Flicker et al, 2007; Alred, 2008; Bell & Bryman, 2007).

Evaluators also routinely grapple with ethical issues, which while also experienced by those conducting some forms of research (e.g. participatory action research), are not found in much academic research. Some of these issues include:

Managing expectations. Many program staff welcome an evaluation as an opportunity to 'prove' that their initiative is having a positive impact. No ethical evaluator can ensure this and it is important the possibility of unwanted findings – and the evaluator's role in articulating these – is clearly understood by evaluation sponsors and affected staff.

Sharing contentious or negative findings. Fear that stakeholders may attempt to manipulate or censor negative results has led to evaluators either keeping findings a secret until the final report is released, or adjusting findings to make them politically acceptable. While the latter is clearly ethically unacceptable, the former also has ethical implications. It is recommended that there are regular reports to stakeholders in order to prepare them for any negative or potentially damaging findings. One of the most important competencies of a skilled evaluator is the ability to speak the truth in a way that is respectful and avoids unnecessary damage to organizations and participants. Some strategies that you may find helpful are to:

Research ethics boards (REBs) vary in how they perceive their role in evaluation. Some, reflecting the view that evaluation is different from research, may decline to review evaluation proposals unless they are externally funded. Other REBs, including institutional boards, require ethical review. This situation can create confusion for researchers. It can also present challenges if researchers feel that their initiative requires REB review (as they are working with humans to generate new knowledge) but there is reluctance on the part of the REB to review their proposal. Unfortunately, there may also be less attention paid to ethical conduct of activities if the initiative is framed as evaluation rather than as research. Some REBs may also have limited understanding of evaluation methodologies, which may affect their ability to appropriately review proposals.