Medicare and Medicaid provide health coverage to 12.5 million individuals who are enrolled in both programs, known as “dual-eligible individuals.” Medicare is their primary source of health insurance coverage, and Medicaid, jointly funded by federal and state governments, provides supplemental coverage. Under the broad umbrella of Medicare coverage, dual-eligible individuals can be covered under a variety of different arrangements, including traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans that are available to all Medicare beneficiaries, and plans that are designed specifically for this population (referred to here as “dual-eligible plans”).

Together, Medicare and Medicaid cover a range of services and financial supports to help meet the diverse needs of the dual-eligible population, which is more racially and ethnically diverse, and more likely to be in poor health than Medicare beneficiaries without Medicaid. At the same time, there are ongoing concerns about a lack of integration of services across the two programs that may contribute to fragmentation of care, poor outcomes, and high costs. In response to these concerns, federal and state lawmakers have been working to develop, test and implement a variety of coverage and financing options to improve coordination of care for this population.

To inform consideration of these coverage and financing options, including what they might mean for how dual-eligible individuals get their Medicare and Medicaid benefits, and who would be most affected, this brief presents national and state-level sources of Medicare coverage for dual-eligible individuals, by demographic characteristics, based on the 2020 Medicare Beneficiary Summary File (See Methods for details and Appendix Table 1).

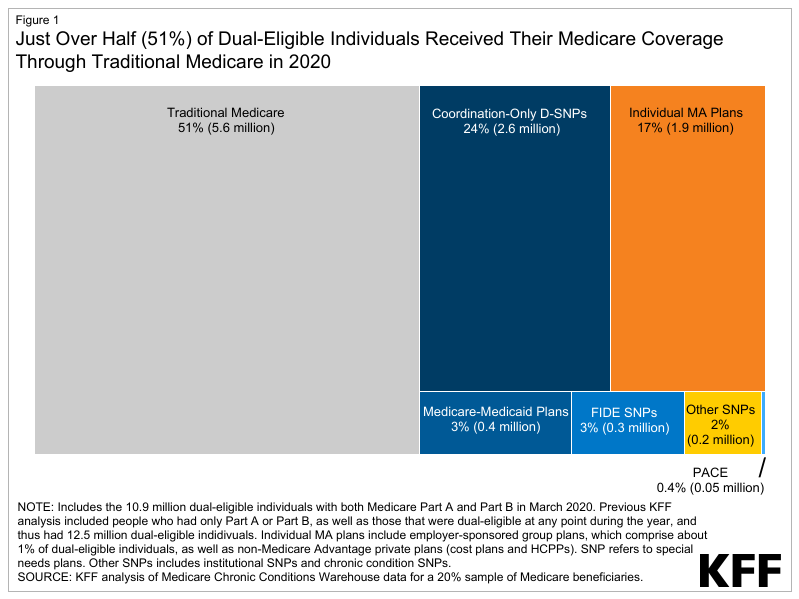

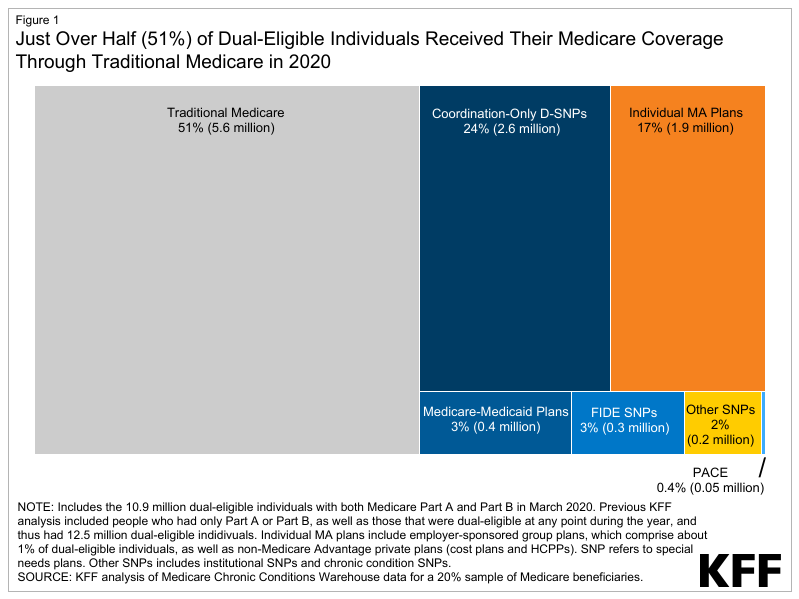

Figure 1: Just Over Half (51%) of Dual-Eligible Individuals Received Their Medicare Coverage Through Traditional Medicare in 2020

Like all Medicare beneficiaries, dual-eligible individuals may choose to receive their Medicare benefits through traditional Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan. This decision may have implications for how dual-eligible individuals receive their Medicaid benefits and the degree to which that coverage is coordinated with Medicare. State Medicaid programs cover benefits that Medicare does not cover, such as long-term services and supports and non-emergency transportation, as well as a broader set of behavioral health services through Medicaid fee-for-service or Medicaid managed care. Most (73%) dual-eligible individuals are eligible for the full range of Medicaid benefits not otherwise covered by Medicare and are referred to as “full-benefit” dual-eligible individuals. Medicaid also provides most full-benefit dual-eligible individuals premium and in many cases, cost-sharing assistance through the Medicare Savings Program. “Partial-benefit” dual-eligible individuals are not eligible for full Medicaid benefits but are eligible for assistance with Medicare premiums and, in many cases, cost sharing, also through the Medicare Savings Programs.

The various Medicare coverage options for dual-eligible individuals are summarized below and in Appendix Table 1.

In traditional Medicare, beneficiaries can obtain care from any provider that participates in Medicare. The payment and delivery of care in traditional Medicare has evolved over the last several decades, with payment including a mix of fee-for-service, bundled, and prospective payments, as well as value-based payment models, such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). ACOs are a group of doctors, hospitals and providers that form partnerships to be collectively responsible for the care coordination of their patients.

Medicare Advantage plans receive a payment from the federal government to deliver Medicare Part A and Part B benefits, and, typically, Part D drug coverage. Medicare Advantage plans often provide some coverage of supplemental benefits, such as vision and dental. These plans are permitted to limit provider networks and may require prior authorization for certain services or referrals for certain types of providers. In this brief, all private plans are referred to as Medicare Advantage plans, including cost contract plans, health care prepayment plans, Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, and Medicare-Medicaid plans. Medicare Advantage plans have been categorized into dual-eligible plans and non-dual-eligible plans (described below).

In this brief, dual-eligible plans are defined as private plans or programs that are designed for people who are dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid and, to varying degrees, coordinate benefits across the two programs. Dual-eligible individuals are not required to enroll in a dual-eligible plan, although in some states, Medicare-Medicaid plans (MMPs) and fully integrated dual-eligible (FIDE) SNPs have the option to passively enroll dual-eligible individuals, which means individuals would need to opt-out if they prefer a different Medicare coverage arrangement. Financing of dual-eligible plans also varies across plan types, and often within plan types depending on the degree of coordination in coverage and benefits.

In this analysis, dual-eligible plans include:

Non-dual-eligible plans are other Medicare Advantage and private plans that may enroll dual-eligible individuals but do not coordinate Medicare and Medicaid benefits. These include individual Medicare Advantage plans that are generally available for enrollment to all people with Medicare, group plans sponsored by employers and unions, and other SNPs for Medicare beneficiaries with specialized health needs, including institutional special needs plans (I-SNPs) and chronic condition special needs plans (C-SNPs).

A smaller share of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in traditional Medicare than the share of Medicare beneficiaries without Medicaid coverage in traditional Medicare (51% vs. 57%, respectively) (Figure 2 and Appendix Table 2).

Of the 10.9 million dual-eligible individuals enrolled in Medicare Part A and B in 2020, 5.6 million were in traditional Medicare and 5.3 million were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans. However, among 5.3 million dual-eligible individuals enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan, the majority (61%) were enrolled in a dual-eligible plan, and the remaining 39% were in a non-dual-eligible plan (data not shown).

Among all dual-eligible individuals, 3 in 10 (30%) were enrolled in dual-eligible plans (Figure 2). Enrollment in dual-eligible plans consisted primarily of enrollment in coordination-only D-SNPs (24%), followed by MMPs (3%), FIDE SNPs (3%), and PACE (0.4%). Higher enrollment in coordination-only D-SNPs than other dual-eligible plan types is likely driven by higher plan availability, since the other types of plans were only available in a limited number of states, and often in a subset of counties in 2020 (e.g., FIDE SNPs, 11 states; MMPs, 9 states; and PACE, 31 states).

About 1 in 5 (19%) dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan that was not designed for people with both Medicare and Medicaid, primarily individual Medicare Advantage plans available to all Medicare beneficiaries (17% of all dual-eligible individuals). Another 2% were in an I-SNP or C-SNP. In 2020, most people enrolled in I-SNPs (91%) were dual-eligible individuals, while just over one-quarter (26%) of enrollees in C-SNPs were dual-eligible individuals.

In 37 states and the District of Columbia, at least 50% of dual-eligible individuals received their Medicare coverage through traditional Medicare in 2020, including 11 states where 70% or more of dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare (Figure 3). The share of dual-eligible individuals in traditional Medicare ranged from a high of 99% in Alaska to a low of 0.3% in Puerto Rico. The share of dual-eligible individuals in traditional Medicare across states was generally similar to the share of Medicare beneficiaries without Medicaid in traditional Medicare, except in 6 states (Arizona, Florida, Hawaii, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Tennessee) and Puerto Rico (Appendix Table 2). For example, in Arizona, 30% of dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare versus 59% of Medicare beneficiaries without Medicaid.

In five states (Arizona, Florida, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Tennessee) and Puerto Rico, more than 40% of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in a dual-eligible plan – higher than the national share of dual-eligible individuals in a dual-eligible plan (30%). In four of these states, the relatively high enrollment in dual-eligible plans was driven by enrollment in coordination-only D-SNPs, including Arizona (39%), Florida (43%), Hawaii (57%) and Tennessee (42%), while in Rhode Island, the enrollment in dual-eligible plans was highest in MMPs (33%). In contrast, in 4 states (Maryland, Montana, North Dakota and Oklahoma), less than 10% of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in a dual-eligible plan (Figure 3, Appendix Table 3).

| Box 1: Medicare and Medicaid in Puerto Rico |

| Puerto Rico is included in this analysis of dual-eligible individuals in Medicare. Notably, Puerto Rico’s Medicare and Medicaid programs differ from the 50 states and the District of Columbia. In Puerto Rico, nearly all Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan. Medicare Advantage penetration is higher across Puerto Rico than in the 50 states and District of Columbia. In 2023 at least 90% of eligible Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan across virtually all Puerto Rican counties. In particular, enrollment in D-SNPs accounts for a much larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollment than in any of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. |

A larger share of Black (54%), Hispanic (65%) and Asian/Pacific Islander (48%) dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans than non-Hispanic White (41%) and American Indian/Alaska Native (25%) dual-eligible individuals. Lower enrollment in coordination-only D-SNPs among non-Hispanic White individuals (16%) compared to Black (28%), Hispanic (37%) or Asian/Pacific Islander (24%) beneficiaries explains lower overall enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans among non-Hispanic White dual-eligible individuals.

A larger share of dual-eligible individuals under age 65 received their Medicare coverage through traditional Medicare than dual-eligible individuals age 65 or older (59% vs 47%) (Figure 5). Higher enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans among dual-eligible beneficiaries age 65 or older compared to those under 65 (53% vs. 41%) is almost entirely accounted for by higher enrollment in individual Medicare Advantage plans (20% vs 13%).

Two-thirds (67%) of dual-eligible individuals living in rural areas received their Medicare coverage through traditional Medicare compared to less than half (48%) of dual-eligible individuals living in metropolitan areas. Traditional Medicare was also the more common source of Medicare coverage for dual-eligible individuals living in a micropolitan area, where 62% were in traditional Medicare. In addition, a larger share of dual-eligible individuals in metropolitan areas were enrolled in coordination-only D-SNPs (25%), FIDE SNPs (3%) and MMPs (4%) than dual-eligible individuals in micropolitan areas (18%, 1% and 1%, respectively) and rural areas (14%, 1% and 0.4%, respectively) (Figure 4).

Among dual-eligible individuals who received full benefits in 2020, nearly 6 in 10 (55%) were enrolled in traditional Medicare, while 45% were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans. For dual-eligible individuals receiving partial benefits, the pattern was reversed, with 58% enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans and 42% in traditional Medicare (Figure 5).

Three in 10 (33%) full-benefit dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in dual-eligible plans, compared to approximately 2 in 10 (23%) partial-benefit dual-eligible individuals. Among full-benefit dual-eligible individuals, enrollment in dual-eligible plans was largely comprised of enrollment in coordination-only D-SNPs (24% of full-benefit dual-eligible individuals), followed by MMPs (5%), FIDE SNPs (4%), and PACE (1%). All partial-benefit dual-eligible individuals in dual-eligible plans were in coordination-only D-SNPs, largely due to enrollment restrictions in other dual-eligible plan types.

A smaller share of full-benefit dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in non-dual-eligible Medicare Advantage plans than partial-benefit dual-eligible individuals (12% vs 35%). Among dual-eligible individuals receiving full benefits, 10% were in individual Medicare Advantage plans, while among those receiving partial benefits, 34% were in individual Medicare Advantage plans.

Consistent with the overall enrollment patterns for full-benefit dual-eligible individuals, in most states (39) and the District of Columbia, more than half of full-benefit dual-eligible individuals were in traditional Medicare. In contrast, in half of states (26), more than half of partial-benefit dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans (Appendix Table 4).

In 2020, one third (30%) of dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan designed for people with both Medicare and Medicaid, 19% were in another Medicare Advantage plan, and just over half (51%) received their Medicare coverage through traditional Medicare. The source of Medicare coverage for dual-eligible individuals varied by state and by beneficiary characteristics.

Dual-eligible individuals have lower incomes, are more racially and ethnically diverse, and often face greater mental and physical health challenges than the general Medicare population, which can make navigating the health care system and health care coverage challenging for this population. Separate eligibility requirements, benefits, and rules for Medicare and Medicaid may further contribute to what has been described as a “fragmented and disjointed system of care for dual eligibles.”

To address concerns about fragmented care and high costs, some policymakers have proposed to expand the role of Medicare Advantage plans that are designed for dual-eligible individuals (or a subset of these plans). Existing Medicare coverage arrangements for dual-eligible individuals vary in the degree of care coordination and integration of financing between Medicare and Medicaid. Some coverage options may offer a greater degree of coordination and financing (such as FIDE D-SNPs) than others. Plans with generally higher degrees of integration tend to have relatively low enrollment nationwide compared with the more common coverage options, in part because they are not widely available.

Proposals that would require dual-eligible individuals to be covered under a Medicare Advantage plan designed for this population would mean a transition from one source of Medicare coverage to another, potentially disrupting care arrangements between patients and providers depending on network restrictions, for the large share of dual-eligible individuals who are covered under traditional Medicare – a group that is disproportionately non-Hispanic White, under the age of 65 with permanent disabilities, living in rural areas, and living in states where enrollment in dual-eligible plans is currently relatively low.

Higher enrollment among dual-eligible individuals in Medicare Advantage plans designed for this population could potentially address fragmentation challenges between Medicare and Medicaid, though based on current evidence, it is not clear these plans always improve the coordination of care. In addition, it is not clear how such changes would affect expenditures under both programs. Assessing the potential effects of various coverage arrangements on the experiences of dual-eligible individuals, and on Medicare and Medicaid spending is beyond the scope of this analysis but would inform consideration of policy proposals that aim to improve coverage and care for this high-need population.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.