When your grandparents used to lament about security or warn you to lock your doors at night that was as far as the concept of “security” went. No one thought an intruder could penetrate a location without physically breaking down doors. Yet today, bank robbers can steal millions of dollars from the comfort of a desk chair. On a household level, this unauthorized accessibility sounds concerning, but when considered by government agencies, the threat is terrifying. While average households possess a small amount of valuable information, governments store millions of records, usually of a sensitive nature. Realizing the potential implications of remote threats, the U.S. Government developed a set of cyber security guidelines called the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA). Are you looking to achieve FISMA compliance ? Continue reading for an overview of the FISMA certification and accreditation process.

In 2002, the president signed the E-Government Act (Public Law 107-347) into effect. The Act outlined the threats information systems face and sought to provide base guidelines for government agencies. Additionally, the Act highlighted the need for tactfully utilizing government resources; a well-designed plan mitigates wasteful or ineffective spending. If agencies understand the types of threats most likely to affect them, the Office of Management and Budget can more efficiently allocate funds. FISMA falls under the E-Government Act (Tittle III). It requires that every federal agency develop, document, and implement an agency-wide program to provide information security for the information and systems that support the operations and assets of the agency, including those provided or managed by another agency, contractor, or other sources. In 2014, the government redefined and updated FISMA to The Federal Information Security Modernization Act due to the rapid advancement of technology and changing cyber threats. The update shifted the primary focus from constant reporting (with little time to properly analyze) to threat monitoring/compliance and reporting when breaches occurred or for a scheduled audit.

The government designed FISMA to ensure that agencies consistently reassess risk and implement security measures based on the level of risk. FISMA applies to all government departments as well as to any associated entities (e.g., contractors). Its process incorporates the following general tasks:

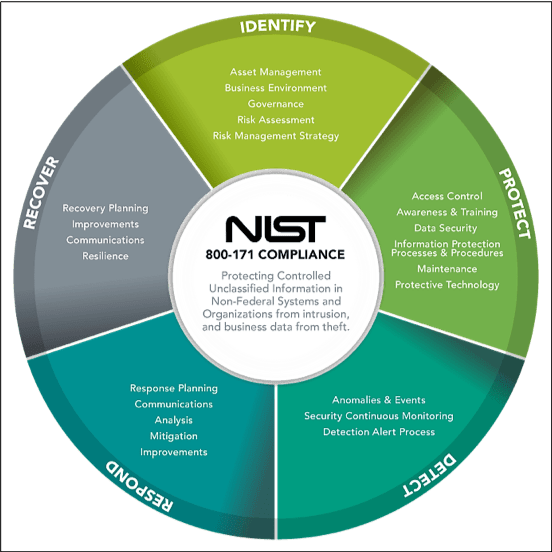

To satisfy these requirements and help agencies better assess internal and external threats, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) produced the Special Publication 800 Series (SP 800) outlining technical specifications and guidelines to support the federal cyber security sector. Such specifications include NIST’s Risk Management Framework and NIST 800-171, which addresses the security requirements for interactions between government agencies and contractors to ensure the protection of “Controlled Unclassified Information.” The NIST 800-171 Compliance Framework , like NIST’s Risk Management Framework, involves 5 phases (identity, protect, detect, respond, and recover), which complement FISMA requirements .

Who must comply? – FISMA requires that all government agencies and associated entities (e.g., contractors) comply with FISMA. However, private companies also benefit from incorporating FISMA into their security plans. In particular, entities seeking government contracts will have a higher chance of securing them if their security policies align with the rigorous government security standards.

FISMA compliance refers to the dual process of Certification and Accreditation (C&A). The FISMA certification process provides the groundwork for accreditation. As understanding and education are key FISMA and NIST concepts, the certification procedure focuses on learning cyber security best practice which enables certified employees to identify weaknesses, change existing security practices, or implement new safeguards. While FISMA’s broad nature means different entities may approach compliance from different angles, understanding the government-approved best practices will help entities build sound security plans.

After initial certification, enterprises must begin the process of implementing FISMA requirements to achieve accreditation. Notably, the C&A process is not a one-time event. Due to the fluid nature of technology and constantly changing threat surfaces, the Office of Management and Budget requires periodic re-certification and re-accreditation for entities that fall under FISMA’s authority. Ron Ross, a lead author of FISMA, likened the C&A process to car inspections every three years. Even if nothing appears to be wrong, it is still mandatory to check all systems and processes.

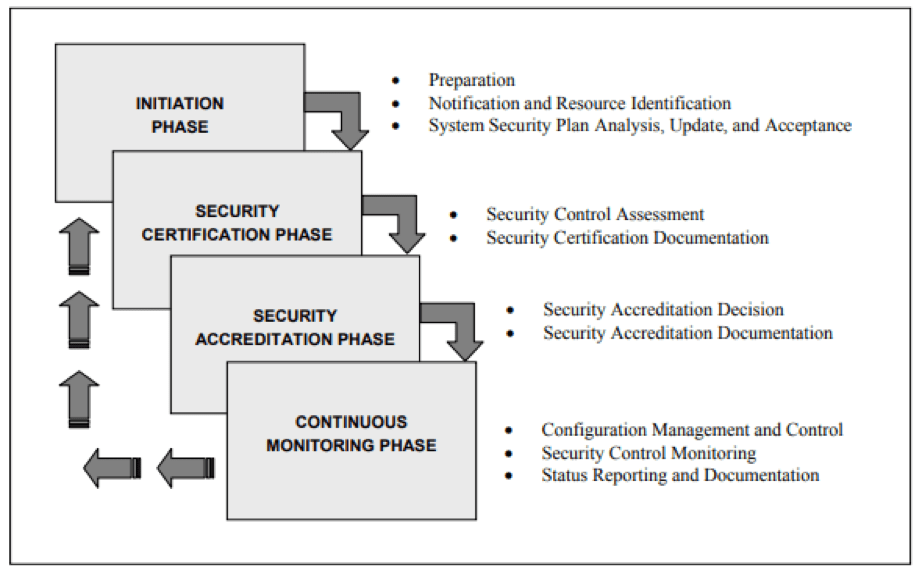

To make the guidelines as straightforward as possible, the FISMA Center divide d the C&A process into four phases as outlined below. If a system does not fall within the confines of a national security system (already designated of high importance), the FISMA Center recommends using the FIPS 199 categories to help select the appropriate NIST security controls needed for a system. FIPS 199 categorizes risks as low, medium, or high impact in terms of how system confidentiality, integrity, and availability will be affected if an attack occurs.

includes preparation, resource identification, and system analysis. This phase makes sure all senior officials are on the same page and agree with the drafted security plan. Prior to gathering key security officers, initial risk assessment, independent audit, and system testing should have been conducted. The extent of these tests will vary depending on if new systems or legacy systems are being reviewed. In other words, the initiation phase serves as a “checkpoint” (confirming the risk assessment was conducted properly) prior to continuing the C&A process. Another key point of this phase involves proper documentation. When conducting the above assessments, FISMA lists approximately 24 points (detailed in the full FISMA report ) that each information system owner should include in the documentation. Examples include the status of a system (e.g., developmental or active), the location of the system/who is responsible for its upkeep, contact information, the functional requirements, and the purpose/capabilities of the system. It is also during this phase that security officers should choose a FIPS 199 level if applicable.

The bottom line questions: Does the FIPS 199 category match the controls outlined in the plan? What resources are necessary and how will they be allocated?

includes security control assessment and certification documentation. During this phase, entities must verify that system controls are properly implemented as outlined in the initiation phase. Additionally, deficiencies in security must be corrected and vulnerability reduced. By the end of the certification phase, risks to the agency, systems, and individuals will be apparent, allowing for informed decision making. FISMA divides security control assessment into 3 sub-phases: prepare, conduct, and document. For example, one pre-assessment step involves reviewing past security test results. The second major component of this phase, documentation, informs the information system owner of vulnerable areas in the system and provides recommendations. Those recommendations ultimately affect the system security plan, as they note which areas need to be updated or given more priority. At the end of this phase, a certification agent will review any security updates or modifications.

The bottom line questions: Are the security controls implemented and operating correctly while also fulfilling the requirements laid out in the initiation phase? If not, how will the plan be adjusted to better reduce system vulnerability? Is the level of risk outlined in the plan applicable to the agency in question?

includes accreditation decision and documentation. During this phase, entities must examine if the remaining risk, after implementing security controls in the previous phase, is acceptable. The information system owner, information system security officer, and certification agent jointly provide information to the authorizing official who, in turn, determines if the final risk level matches the “acceptability of risk” ranking. When determining the acceptable level of risks, the authorizing officer takes into consideration the agency’s mission and operation activities. In addition, the officer will likely consult key officials to gain better insight. The goal of this phase focuses on achieving “authorization to operate.” However, an “interim authorization to operate” may be issued if the officer deems the level of risk unacceptable. This type of authorization allows an agency to continue critical operations, but requires it to submit a new security accreditation packet. If corrections fail are not completed by the deadline specified, accreditation will not be granted. If revisions are required, authorizing officials (i.e., those in charge of the C&A process) must document any revisions to the security plan. By the end of this phase, all documentation from the previous phases must be compiled into a final security accreditation package, including an accreditation decision letter. The final package must then be disseminated to any relevant officials.

The bottom line questions: How does the level of risk affect agency operations, assets, or individuals, and is that level of risk acceptable?

includes system configuration, security management, monitoring, and reporting. This phase focuses on maintaining a high level of security by monitoring security controls, documenting any updates, and determining if any new vulnerabilities develop. If an agency implements significant changes to a security plan, reaccreditation may be required (or due to a scheduled/mandatory reaccreditation review). This process requires detailed documentation, such as detailing the current hardware, software, or firmware version in use. Furthermore, officers must note physical modifications (e.g., new computers or facility access changes). Responsibility for many of these tasks falls to the information system owner. The level of monitoring each threat vector receives should mirror the priorities of the agency. Thorough monitoring encompasses a configuration check, operational verification, and desired output confirmation. As with all phases, after a review is completed, the security package must be updated to reflect the modifications.

The bottom line questions: Have any modifications occurred or new vulnerabilities been identified? Has the level of risk changed significantly based on these findings? Is it time for reauthorization based on federal/agency policy?

FISMA Center Security and Accreditation Process Summary

Although there are many ways to approach FISMA compliance, the overlapping nature of FISMA and NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework make combining the two sets of guidelines a viable option. In fact, many of NIST’s resources were designed with FISMA in mind. NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework begins with the Identification Phase , and FISMA begins with the Initiation Phase . Since NIST recommends selecting an individual(s) to oversee the process, it would be beneficial for this person to also become FISMA certified. Having a department head who is knowledgeable about both FISMA and NIST will make the process of compliance much easier. The FISMA Center offers training materials and a testing schedule. Since it is unlikely all employees will become FISMA certified, those who successfully complete the certification course should pass on their knowledge, making employees aware of the most current types of attacks and training them in correct incident response procedures.

NIST Framework Basics

Likewise, NIST’s Protect and Detect Phases pair well with FISMA’s Assessment/Implementation Phase . NIST’s guidelines provide detailed outlines for what areas to review (internal and external assessment) which will help provide the groundwork for creating a sound FISMA accreditation plan. In particular, utilizing NIST’s Risk Management Plan helps agencies or businesses determine their appropriate level of acceptable risk. Before implementing new security measures, agencies and businesses must understand their weak spots and analyze which safeguards work well and which need improvement. Topics to consider include identification and authentication practices (e.g., need to know access), system configuration (e.g., firewalls), physical security, and communication integrity. Furthermore, FISMA/NIST breaks security controls into low, medium, and high impact categories, helping entities determine which areas are priorities and how to best allocate resources in the assessment phase (similar to the FIPS 199). This flows directly into the planning process. After thorough assessment, entities can begin formulating a protection plan. Lastly, NIST’s Detect , Respond, and Recover Phases complement FISMA’s Monitoring Phase, as monitoring requires both a well-oiled process for reporting anomalies and clear guidelines for how to recover critical, operational capabilities in the event of an attack.

The complete report on FISMA C&A provides much more detail than the above summarization. Each phase outlines numerous tasks and subtasks for more comprehensive review. To learn more about how FISMA C&A relates to your company or to receive assistance in other cybersecurity solutions , contact RSI Security today.