The evolution of ideas in global climate policy

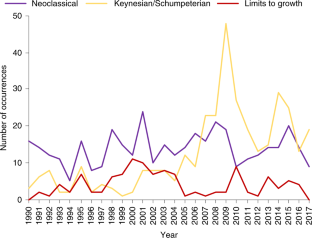

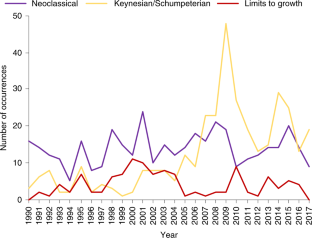

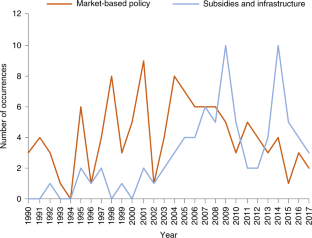

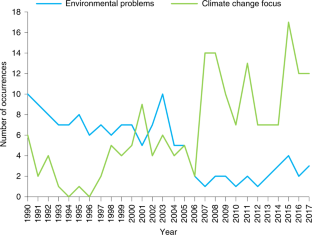

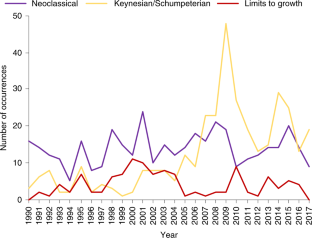

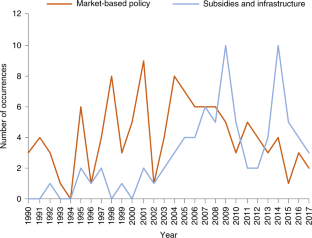

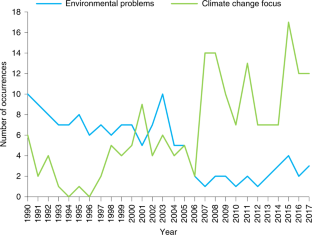

From carbon pricing to green industrial policy, economic ideas have shaped climate policy. Drawing on a new dataset of policy reports, we show how economic ideas influenced climate policy advice by major international organizations, including the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Bank, from 1990 to 2017. In the 1990s, the neoclassical notion of weak complementarity between environmental protection and growth dominated debates on sustainable development. In the mid-2000s, economic thought on the environment diversified, as the idea of strong complementarity between environmental protection and growth emerged in the green growth discourse. Adaptations of Schumpeterian and Keynesian economics identified investment in energy innovation and infrastructure as drivers of growth. We thus identify a major transformation from a neoclassical paradigm to a diversified policy discourse, suggesting that climate policy has entered a postparadigmatic period. The diversification of ideas broadened policy advice from market-based policy to green industrial policy, including deployment subsidies and regulation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

206,07 € per year

only 17,17 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Policy sequencing towards carbon pricing among the world’s largest emitters

Article 24 November 2022

Policy spillovers from climate actions to energy poverty: international evidence

Article Open access 29 August 2024

Climate economics support for the UN climate targets

Article 13 July 2020

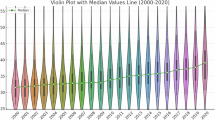

Data availability

The data are available in the Supplementary Data. The source data for Figs. 1–4 are also available as supplementary files.

References

- Bernstein, S. The Compromise of Liberal Environmentalism (Columbia Univ. Press, 2001).

- Jacobs, M. in The Handbook of Global Climate and Environmental Policy (ed. Falkner, R.) 197–214 (John Wiley & Sons, 2013).

- Tienhaara, K. Varieties of green capitalism: economy and environment in the wake of the global financial crisis. Environ. Polit.23, 187–204 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bäckstrand, K. & Lövbrand, E. The road to Paris: contending climate governance discourses in the post-Copenhagen era. J. Environ. Policy Plan.21, 519–532 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lövbrand, E. & Stripple, J. Making climate change governable: accounting for carbon as sinks, credits and personal budgets. Crit. Policy Stud.5, 187–200 (2011). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stripple, J. & Bulkeley, H. New Approaches to Rationality, Power and Politics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

- Pearce, D., Markandya, A. & Barbier, E. B. Blueprint for a Green Economy (Earthscan, 1989).

- Antal, M. & Karhunmaa, K. The German energy transition in the British, Finnish and Hungarian news media. Nat. Energy3, 994–1001 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Thornberg, R. & Charmaz, K. in The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Content Analysis (ed. Flick, U.) 153–169 (Sage, 2014).

- Schreier, M. in The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Content Analysis (ed. Flick, U.) 170–183 (Sage, 2014).

- Bina, O. The green economy and sustainable development: an uneasy balance? Environ. Plan. C31, 1023–1047 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ferguson, P. The green economy agenda: business as usual or transformational discourse? Environ. Polit.24, 17–37 (2014). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Death, C. Four discourses of the green economy in the global South. Third World Q.36, 2207–2224 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stevenson, H. Contemporary discourses of green political economy: a Q method analysis. J. Environ. Policy Plan.21, 533–548 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Georgeson, L., Maslin, M. & Poessinouw, M. The global green economy: a review of concepts, definitions, measurement methodologies and their interactions. Geo4, e00036 (2017). Google Scholar

- Borel-Saladin, J. M. & Turok, I. N. The green economy: incremental change or transformation? Environ. Policy Gov.23, 209–220 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nordhaus, W. D. Resources as a constraint on growth. Am. Econ. Rev.64, 22–26 (1974). Google Scholar

- Hartwick, J. M. Intergenerational equity and the investing of rents from exhaustible resources. Am. Econ. Rev.66, 253–256 (1977). Google Scholar

- Solow, R. M. The economics of resources or theresources of conomics. Am. Econ. Rev.64, 1–14 (1974).

- 1991 UNDP Annual Report: The Challenge of the Environment (UNDP, 1992).

- Informal Meeting of the G7 Environment Ministers (G7, 1994).

- The World Bank Annual Report 1995 (World Bank, 1995).

- Hajer, M. A. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process (Clarendon, 1995).

- The Global Environmental Facility: A Self-Assessment (World Bank, 1996).

- Newell, P. & Paterson, M. Climate Capitalism: Global Warming and the Transformation of the Global Economy (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

- Ciplet, D., Roberts, J. T. & Khan, M. R. Power in a Warming World (MIT Press, 2015).

- World Bank World Development Report 1992: Development and the Environment (Oxford Univ. Press, 1992).

- IPCC Climate Change 1995: Synthesis Report (eds Bolin, B. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1996).

- Michaelowa, A. & Michaelowa, K. Climate business for poverty reduction? The role of the World Bank. Rev. Int. Organ.6, 259–286 (2011). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Skovgaard, J. EU climate policy after the crisis. Environ. Polit.23, 1–17 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gravey, V. & Jordan, A. Does the European Union have a reverse gear? Policy dismantling in a hyperconsensual polity. J. Eur. Public Policy23, 1180–1198 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stern, N. Lionel Robbins Memorial Lecture Series:How We Can Respond and Prosper: The New Energy–Industrial Revolution (LSE, 2012).

- Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., Bursztyn, L. & Hemous, D. The environment and directed technical change. Am. Econ. Rev.102, 131–166 (2012). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Acemoglu, D., Akcigit, U., Hanley, D. & Kerr, W. Transition to clean technology. J. Polit. Econ.124, 52–104 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barbier, E. B. A Global Green New Deal: Rethinking the Economic Recovery (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

- Edenhofer, O. & Stern, N. Towards a Global Green Recovery (PIK and LSE, 2009).

- Bowen, A. & Stern, N. Environmental policy and the economic downturn. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy26, 137–163 (2010). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Annual Report 2006 (OECD, 2006).

- Green Growth: Overcoming the Crisis and Beyond (OECD, 2009).

- UNEP Climate Change Strategy (UNEP, 2009).

- UNEP Annual Report 2011 (UNEP, 2012).

- Secretary-General’s Report to Ministers 2016 (OECD, 2016).

- G7 Environment Ministers Meeting Communiqué (G7, 2016).

- Farrell, H. & Quiggin, J. Consensus, dissensus, and economic ideas: economic crisis and the rise and fall of Keynesianism. Int. Stud. Q.61, 269–283 (2017). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- A Global Green New Deal: Policy Brief (UNEP, 2009).

- Barbier, E. B. Rethinking the Economic Recovery: A Global Green New Deal (UNEP, 2009).

- Annual Report 2011/2012: The Sustainable Future We Want (UNDP, 2012).

- Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Seventeenth Session (UNFCCC, 2011).

- Dimitrov, R. S. The Paris Agreement on climate change: behind closed doors. Glob. Environ. Polit.16, 1–11 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Twenty-First Session (UNFCCC, 2015).

- Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J. & Behrens III, W. W. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind (Universe Books, 1972).

- Daly, H. E. The economics of the steady state. Am. Econ. Rev.64, 15–21 (1974). Google Scholar

- Policies to Promote Technologies for Cleaner Production and Products: Guide for Government Self-Assessment (OECD, 1995).

- Annual Report 2001 (OECD, 2001).

- Bernstein, S. in Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Governance and Politics (eds. Pattberg, P. H. and Zelli, F.) 45–52 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015).

- Hale, T. Catalytic Cooperation Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper BSG-WP-2018/026 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2018).

- Falkner, R. The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics. Int. Aff.92, 1107–1125 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hall, P. A. Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: the case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comp. Polit.25, 275–296 (1993).

- Hogan, J. & Howlett, M. in Policy Paradigms in Theory and Practice: Discourses, Ideas and Anomalies in Public Policy Dynamics (eds Hogan, J. & Howlett, M.) 3–18 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Agopian, M. Conner, R. Jacobson and Z. Woogen for research assistance. We thank S. Bernstein, M. Kocher and M. Paterson for excellent comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA Jonas Meckling

- Department of Political Science, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA Bentley B. Allan

- Jonas Meckling